Paul Schneider

This is not my article. I did not write it. I copied it here as part of my attempt to compile articles about rarely heard Men of God. The publishers can be found at http://www.epbooks.org/

October 5, 2012

Paul Schneider – German opponent of Hitler

From WAR AND GRACE – Short biographies from the World Wars, by Don Stephens, published by Evangelical Press, Faverdale North, Darlington, DL3 0PH, England.

Throughout 1915 the First World War raged in both western and eastern Europe. In the German onslaught in the east against Russia, Paul Robert Schneider, an eighteen-year-old German soldier, received a serious wound in the stomach. For his bravery he was awarded the Iron Cross.

After surgery and recovery from it, Paul Schneider fought in the artillery against Britain and France. His courage did not go unrecognized. By the end of the war he had risen to the rank of lieutenant. At about the same time another German soldier ended the war as a corporal. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Adolf Hitler is now regarded as one of the most evil men who has ever lived. For twelve years, from 1933 to 1945, his political party, the National Socialists, or Nazis, dominated the life of Germany. For many years after 1933 his following among the German people was almost complete. Cheering crowds greeted him with rapturous enthusiasm whenever he appeared in public. He was idolized like a god. His power was so great that he led his people into an aggressive war in which millions died. His legacy to the country he ruled as a dictator was ruin and shame.

During those fateful years, the opposition to Hitler within Germany was so small that it was crushed with ease. Those who openly protested against Nazi ideology or policies paid a heavy price. The great scientist Einstein pointed out the origins of the most effective resistance. ‘Only the Church stood squarely across the path of Hitler’s campaign to suppress truth…it had the courage to stand for intellectual truth and moral freedom.’

When Germany was defeated in 1918, Paul Schneider decided to give up his original plan to be a physician. His father, Gustav-Adolph, was a pastor in the German Evangelische Reformierte Kirche, a church that is Presbyterian in organization and belief. Paul’s decision to study theology at this time probably had a great deal to do with the influence of his family background.

It is not surprising the years immediately after the war were a time of mental turmoil for him. Since schooldays he had been taught the critical view of the Bible. This held that it was full of mistakes and could not be trusted. He was also troubled by the appeal of Communism and Socialism. As a German, he did not like the parts of the Treaty of Versailles that allegedly humiliated his country. He struggled spiritually, yet it was clear to him that, unless people’s hearts were changed, a new tyranny would merely replace an old one like that of the Kaiser.

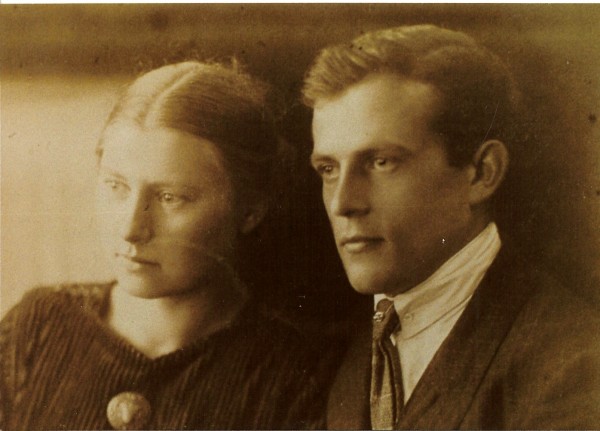

Just before Christmas in 1921, as his theological studies began, his spiritual struggles came to an end. He rejected his positive view of human nature, which he realized was derived form nineteenth-century optimism. The Reformers Luther and Calvin were right: man is a sinner in need of redemption. The Bible is not just religious folklore; it is the Word of God. Gretel, the young lady who was to become his wife, recorded: Eternal life entered his soul and he was filled with great joy.

From his diaries and letters we know that he experienced a definite personal conversion to Christ. Now he had a message to preach: the biblical gospel that salvation is by repentance and faith in the crucified and risen Christ. He could see the Reformation confessions of his church not just as historical documents, but also as statements of his faith. Later on, when in prison, he asked his wife to let him have the Belgic confession and the Heidelberg Catechism to study alongside his Bible. Paul Schneider had become a Reformed evangelical Christian.

During the demanding preparation to be a pastor, he felt the need to experience the life of an ordinary workingman. An uncle heard of his plan to work in a factory for a while, and offered him a comfortable, well-paid job. But he did not want a ‘soft’ job. So throughout most of 1922 Paul Schneider became part of a gang of workers at a blast furnace near Dortmund. He said that he needed to understand the demands of the daily grind such men face. They showed him their respect and on the day he left said, ‘You are one of us. Try to stay like that.’ He did.

The years before his ordination were filled with study at university and theological college. For nine months up to July 1924 he worked for the Berlin City Mission, becoming acquainted with poor and wretched men and women, some of them addicted to alcohol and drugs.

Ordination followed in 1925. For a time he was an assistant pastor in Essen. In 1926 his father suffered a stroke while preaching and died three days later. His father’s church at Hochelheim unanimously called Paul to succeed him as pastor. He had been married less than a month when he was installed as pastor in September 1926. His first sermon was based on 2 Timothy 3:14-17, the heart of which declares that all Scripture is God-breathed, which means that it is without error – that is, infallible. The choice of this passage indicates his belief in the authority of the Bible alone. He was Reformed in his faith and his ministry was Bible-based. All surviving accounts indicate that he was a bold and powerful preacher.

He also had a real loving concern for the people. There are descriptions in existence of the sick listening for the distinctive whine of his motorcycle on his way to visit them. Gretel, his wife, records that in their dying moments some testified that Paul Schneider was the one used by God to bring peace through leading them to faith in Christ.

In Gretel’s memoir of Paul there is another story from that period. A young epileptic had a very severe attack, which went on for three days and nights. In spite of strong narcotics, nobody could give him rest. Then Paul Schneider arrived. He prayed for the helpless boy and spoke quietly to him. Peace came and the boy fell asleep. Later Schneider returned once more at just the right moment. ‘I knew I was needed here,’ he said as he arrived. Just as the boy died peacefully in Paul’s arms he said clearly, ‘I thank you all for everything, but that I can die at peace with my God and with no fear of the grave, I thank our pastor.’ The pastor knew where the power came from. His diary says, ‘I am utterly dependent on the grace of God alone.’

Paul Schneider was an example of a minister who was rarely off duty. His work was his life. We see him trying to win young people to Christ by playing sports or going on rambles with them. Older folk working in the fields would find him joining the work of harvesting or haymaking. He built up his relationships with the local people. Yet within his congregation he believed in applying Biblical church discipline to a few who had scandalous lifestyles and came to the Lord’s Table as though they were doing nothing wrong.

On 30 January 1933 Hitler came to power, and life in Germany began to change. Of the one thousand people in Schneider’s rural Rhineland parish of Hochelheim, half freely voted for the Nazis. Nevertheless, from an early stage of Nazi rule, Paul Schneider spoke out against wrong policies and actions. He would never use the greeting, ‘Heil Hitler’, quite reasonably considering it a form of idolatry.

So-called ‘Christians’ who accepted Nazism were known as ‘German Christians.’ Schneider would have nothing to do with them because they accepted Hitler’s anti-Semitic policies. Eventually Paul Schneider put some criticisms of Nazism on his church bulletin board and was forced to account for what he said to a ‘German Christian’ leader. This man was dressed in Nazi uniform and had a huge cross dangling on his chest. Paul could see that these people were trying to force the church to adopt Nazi ideas. Sadly, the leaders of the Hochelheim Church would not support him in his stand. As a result, he was forced to take a new pastorate with two churches, one in Dickenschied and the other nearby in Womrath.

Paul Schneider was installed as minister in May 1934, at the age of thirty-six. He had been in his new pastorate for only a few weeks when faithful men who thought as he did issued the Barmen Declaration. Part of the wording of this declaration defiantly asserted: ‘Jesus Christ, as he is attested for us in Holy Scripture, is the one word of God which we have to hear and which we have to trust and obey in life and in death.’

Just over a month after he began his new ministry a completely unexpected incident occurred. Tuesday, 12 June, dawned as just another beautiful early summer day in rural Rhineland. As Schneider travelled to nearby Gemünden to stand in for another pastor at a funeral service, he had no idea of the trouble that lay ahead.

Wearing his simple black clerical robe, Paul Schneider walked in front of the bearers of the coffin towards the open grave. Ahead of him could be seen a parade of the Hitler Youth organization with bands and flags. He recalled that the dead seventeen-year-old youth had told him that he was the first young man in Gemünden to join the Hitler Youth. Paul conducted the graveside service, but before the committal and without asking permission, the local Nazi leader, Heinrich Nadig, spoke at some length and then asserted, ‘Comrade Karl Moog, you have now been enlisted in Horst Wessel’s battalion in heaven.’

As Paul stepped forward to pronounce the benediction, he knew that something must be said to make it clear to the hundreds of youthful Nazis that Horst Wessel was not part of a Christian burial. As reasonably as he could he explained the truth of the gospel and rejected the idea that there is a Horst Wessel group in heaven.

The local Nazi leader then approached the coffin and half addressing the crowd and half addressing the dead youth, he insisted, ‘Comrade, whatever they say, you are now enlisted in Horst Wessel’s battalion.’ Paul Schneider protested and reminded the Nazi leader that he was at a church service. The Nazi stormed away and the parade broke up.

The day after the funeral Schneider was arrested and imprisoned for a week. On his release he was given a strong warning to stop opposing the wishes of the state.

What was the Nazi thinking in all this? They had revived old pagan legends, one being the Viking myth that at death the individual joins other departed warriors. They idolized various folk heroes. Horst Wessel was a Nazi who had been shot in a street fight with political enemies in 1930. He became a Nazi folk hero, and was glorified as a martyr. The Horst Wessel song, full of pagan sentiments, was often sung at rallies when Hitler was present.

When the pastor made his graveside protest against Nazi ideology, he was holding to the right of the church to defend the purity of Christian truth. While in prison he informed the Nazi officials that he did not intend to be antagonistic to the state, but if there was to be harmony between church and state, the Nazis should respect the rights of the church to maintain the truth of the gospel. He had embarked, single-handed for all he knew, on a collision course with an increasingly dominant police state.

During the winter of 1935-36 the Nazis rebuked Paul Schneider on twelve occasions. They resented the fact that faithful Christians had organized themselves into the ‘Confessing Church’. This body issued a statement that was intended to be read openly in faithful gospel churches. The Gestapo, the State Secret Police, visited Paul and put pressure on him to sign a document agreeing not to read it publicly. True to his principles, he refused. For that, he was imprisoned for four days.

Paul Schneider also resisted the pressure that was put on Christian youth movements to integrate into the Hitler Youth. Somebody reported him for not using the ‘Heil Hitler’ salute at his confirmation classes. He considered the salute as idolatry and would not use it on principle. Schneider particularly loathed the hate propaganda against the Jews. His church had an organization that was a mission to German Jews. When he went ahead with his usual collection for the mission to the Jews, Nazi feelings were inflamed against him. Later this Nazi anti-Semitism would lead to the Holocaust, an undisguised attempt at total genocide.

In the early hours of 7 March 1936 Hitler ordered German troops to occupy the Rhineland. One of the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles was that part of the Rhineland was to be demilitarized. By sending German soldiers to seize it back, Hitler was openly defying the peace treaty. The world held its breath. Rather than cause another war, Hitler was allowed to win. He was jubilant at his success. Most Germans agreed with him. Many historians now think that if the Allies had resisted Hitler over the Rhineland incident, he might have acted differently when it came to seizing lands that were not German territory.

The Nazis organized a ballot supposedly to indicate whether citizens approved of Hitler’s illegal action. The ballot paper had no place to say ‘No’, so the inevitable result was ninety-nine percent in favour of Hitler. On the day of the vote, Nazi police visited Paul and Gretel to try to persuade them to vote. Their decision not to vote was one more major accusation that was levelled against the rebel pastor.

To be a Nazi and to be a German patriot had become the same thing for most people in the land. Paul Schneider was a patriotic German. His hard-won war medal proved that he would fight for his country, but now he was opposing a military-backed dictatorship. Trade unions had been abolished. The media were in the grip of the Nazi party. Textbooks were rewritten. Human biology was dominated by the Nazi belief that some races were ‘higher’ and that they would eliminate ‘lower’ races by force. By the time of the vote, Hitler had supreme power. He was Fuehrer (Leader) of the whole nation and all the armed forces. There was a lot of evidence to support what Paul Schneider said at the time. ‘National Socialism becomes more obviously opposed to biblical Christianity every day.’

The sermons he preached were powerful. Often they included passages like this: ‘Do not deceive yourselves, you cannot participate in Jesus’ glory and victory unless you, for his sake, take up the holy cross and go with him along the path of suffering and death.’

By the summer of 1936 the Schneiders had a family of four boys and a girl – and their education intensified his troubles. Both his churches had single-class church schools attached to them. The two teachers had joined the Nazi party and used their positions to indoctrinate the children. Paul Schneider tried to intervene. After all, they were church-based schools, and he was the father of five of the pupils.

As a result, Nazi police searched his house. Papers and sermon notes were taken away and not returned. Doubtless this was because some of his sermons contained references to ways in which Nazism and the Bible were in disagreement. The Gestapo dossier of his opposition to Nazi beliefs and policies grew ever bigger.

On most days he was out and about using his motorcycle for pastoral visits. One evening in March 1937, he was returning home after taking a confirmation class at Womrath. He did not arrive at the expected time. Gretel received the news that in the dense fog he had collided with an unlit farm trailer carelessly parked on the road. His left leg was broken in three places and had to be put in a plaster cast. He was kept in hospital.

A little while later his sixth child was born. Paul wrote a poem, as he often did to celebrate important events. Interestingly, they named the child Ernst Wilhelm, the names of two of Gretel’s brothers killed while fighting the British at the Battle of Somme in 1916.

On 3 May 1937 two Gestapo agents burst into his study and arrested him. His general health was not good because his leg had only been out of plaster for a few days. They gave him no time to pack any belongings. Gretel was informed that he would be taken to nearby Koblenz for questioning.

He was held in an underground cell. There was no charge, no questioning and no trial. The reason given for his arrest was that he was a danger to public order. In the world of the Gestapo he became ‘Prisoner Schneider’, not ‘Pastor Schneider’. In an attempt to intimidate him, he was treated like a common criminal by having his photograph taken from every angle and his fingerprints recorded. Eventually he was allowed to write to Gretel. She was urged not to worry about him because ‘All is in God’s hands and he will use the matter…’ Although he would be present only in spirit, he urged Gretel to go ahead with the baptism of the sixth child. Another long poem celebrated the birth of the child and the baptism.

After eight weeks he was released. However, there was a condition. He must accept an expulsion order from the Rhineland. Paul made it absolutely clear that he could not accept the legality of such an order that would separate him from his home and his churches. After all, there had been no trial, just the so-called ‘law’ of the Gestapo. To make their point, the Nazis bundled him into a car, drove him fifty miles to Wiesbaden, just over the Rhineland border, and left him there. To make his point Paul put the illegal banishment papers in a rubbish bin and caught the first train home. He was taking a big risk.

When he arrived home he looked ill; he was exhausted and his leg needed medical attention. Friends persuaded him to go for treatment and convalescence at Baden Baden, which lay outside the Rhineland. Here he was safe. Outwardly it appeared that he accepted the banishment order.

After a week Gretel joined him. Her hope was that he would give in to the Gestapo and find a church outside the Rhineland. Paul, however, had made a firm decision while in the Gestapo prison at Koblenz. He would resist unjustified bullying. With questioning in her mind, Gretel reminded him that if he went back to his Dickenschied pulpit, he would be rearrested. Paul quoted some words from a Bible verse to her. They came from Judges 5:18 and said, translated literally, ‘Zebulun…and Naphtali…risked their lives to the point of death.’ Hearing him quote this, Gretel hung her head in despair. Her voice quivered as she asked, ‘Paul, don’t you think about the children and me? Paul, don’t you love us?’

Paul’s eyes filled with tears. With powerful arms he hugged Gretel to his chest. ‘My darling’, he sobbed, ‘I have never loved you or the children more than on that night of decision. I wept for you.’ With those words, spoken with such deep emotion, pathos and conviction, Gretel knew that her only choice was to indentify herself with her husband.

It was 5 October 1937, Harvest Festival Sunday. Paul Schneider returned to Dickenschied. His family and friends were overjoyed to see him. However, the well-informed people knew he was taking a risk. He preached at Dickenschied in the morning on Psalm 145:15-21. Did he have any idea that it would be his last pulpit message – that the very act of preaching in his own church would lead to the loss of all he held dear? He went by car to Womrath to take the evening service. Police cars with flashing lights blocked the road. As he was arrested, he called out to Gretel: ‘Tell the church that I am and shall remain the pastor of Dickenschied and Womrath.’ Gretel just had time to push a Bible into his pocket.

He was held for some time in Koblenz prison, constantly being urged to sign a document agreeing to banishment. ‘What do you do all day?’ asked Gretel in one letter. His answer was: ‘I am a pupil in the school of God’s Word.’

Behind the scenes the faithful church, the ‘Confessing Church’, was facing enforced closure of all its work. It did not have the power to help Paul Schneider, one of its most distinguished members. Its best known leader, Martin Niemöller, a Lutheran pastor who had once captained a First World War U-boat, was himself in prison. Schneider and Niemöller shared the dubious distinction of being Hitler’s ‘personal prisoners’, meaning that he had personally signed the order to silence them. The official reason given by the Nazis for suspending anyone’s liberty was always ‘to defend the state’. Effectively, the Gestapo had absolute power about who could be arrested, and what to do with protestors. Those in prison paid for their own captivity by the confiscation of all assets. It was a good thing Paul lived in a house he did not own. Even the garden had been purchased in Gretel’s name only.

On 25 November 1937 Paul Schneider was taken to Buchenwald Concentration Camp near Weimar, about 200 miles from his home in Dickenschied. Gretel and the children said a final farewell. The image of her husband smiling and waving as he was driven away stayed forever in Gretel’s mind.

Karl Koch, the Nazi in charge of the camp, had total power over the inmates. The guards constantly taunted Schneider. As one man said, ‘The walls of his prison were made of paper.’ In other words, if he would agree to sign a document relinquishing care of his churches and accept banishment, he could go free. Just consider the immense pressure on him to sign and go back to his family!

From the beginning he had no privileges. Like the others, he worked sixteen-hour shifts. Constantly he maintained his Christian witness. He fasted every Friday and gave his meagre food ration to others.

20 April 1938 was Hitler’s forty-ninth birthday. To honour him, the prisoners were lined up and ordered to remove their berets and venerate the Nazi swastika flag. As one man the parade whipped off its headgear. The guards noticed the solitary figure who would not bow to the swastika – Paul Schneider. For this he was viciously struck twenty-five times with an oxhide whip. His bleeding body was left in solitary confinement. Here he stayed for the next fifteen months. The cell was four feet wide and ten feet long (1.2 metres by 3 metres). There was no furniture, no electric light, and all he ever had to eat was bread and water. Before long he became a broken skeleton. His clothes became rags and his body crawled with vermin. Nor was he allowed a Bible.

On the morning of Sunday, 28 August 1938, Paul Schneider preached through the bars of his cell to men lined up for the 06.30 roll call. Survivors recorded what he said: ‘Our Lord Jesus Christ came into the world to save us from our sins. If we have faith in him, we are put right with God. We need not fear what man may do to us because we, through Christ, belong to the kingdom of God…Our Lord Jesus Christ who died for us has promised that we, by faith in him, may participate in his resurrection. He said, “I am the resurrection and the life. He that believes in me shall never die.” Accept the Lord Jesus as your Saviour, and God will receive you as his child…”

After two minutes guards rushed into his cell and pulled him away from the bars of the window. For this message he was once again tied to a rack and suffered another twenty-five strokes of the whip. Schneider’s response to a friend was: ‘Somebody has to preach God’s word in this hell.’

In January 1939 two prisoners who tried to escape were hanged in front of the assembled inmates. Paul Schneider called out through his cell window: ‘In the name of Jesus Christ, I witness against the murder of these prisoners…’ The response was another twenty-five lashes.

A guard said to him, ‘If we released you, what would you do?’ Seeing in his mind’s eye the image of two men hanging on the gallows, Paul replied, ‘I would go to Weimar [the nearest town] and the first kerbstone would become a pulpit from which I would denounce the brutal crimes committed here.’ For saying that, he was suspended by his wrists from the window bars, with his feet off the floor, for hours.

He continued his brief messages through the cell window. One prisoner recalled Paul Schneider preaching the message of new life in Christ on Easter day 1939. Another who survived later commented: ‘In my estimation he was the only man in Germany who, overcoming all human fear, so consciously took on himself the cross of Christ even to death.’ Every time he preached from his bunker, his tortures increased, but his faith in the Lord grew stronger.

Finally, on 18 July 1939, the starved, beaten, bleeding Paul Schneider died when the camp doctor injected a massive overdose of strophanthin. Paul was forty-one years old. Gretel became a widow at the age of thirty-five.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a definite opponent of the Nazis, received the news of Schneider’s death in 1939. At the time he was staying in London with his sister Sabine. The Christian writer and theologian said to his nieces and nephews, ‘Listen children. You must never forget the name of Pastor Paul Schneider. He is our first martyr.’ (Bonhoeffer himself later returned to Germany and was hanged by the Nazis in 1945.)

The telegram to Gretel from the Buchenwald commandant said, ‘Paul Schneider, born 29 August 1897, died today at 10.40 a.m. If transport of the body at the family’s expense is required, a request must be made within twenty-four hours … otherwise the body will be cremated.

Gretel arranged for the body to be brought home. Three days after his murder, Paul’s remains were buried in the churchyard at Dickenschied. In less than two months Hitler’s plan to begin the nightmare of the Second World War would take effect.

Gretel and the six children survived the horror of that war. She lived as a widow until her death on 27 December 2002, twelve days before her ninety-ninth birthday. She lived to see all her children grow up, and her husband become respected as a martyr by the Evangelical Church of the Rhineland. There is even a Pastor Paul Schneider Association, founded at Weimar in 1997, dedicated to keeping his memory alive. Visitors to his cell in the bunker at Buchenwald can now see his photograph, a plaque in honour of his sacrifice and the words of a biblical text selected by his widow: ‘We are … Christ’s ambassadors, as though God were making his appeal through us. We implore you on Christ’s behalf: Be reconciled to God’ (2 Corinthians 5:20).

Comments

Post a Comment